Abstracting From Observation

Picasso, Still life 1960, Collotype

There are many ways to begin an abstract painting. Creating shapes is the priority, and how you find those shapes can happen in different ways. Many times when I begin a painting I start with a busy layer of oily smudges and splotchy piles of color. It's chaos. I apply too many colors, make too many marks, and churn out a lot of irregular drawing lines. It's an effective way to activate the canvas and have plenty of information to respond to. Chaos to organization. This approach can also make one feel especially lost...a feeling all abstract painters become accustomed to.

There are other times when I begin with a reference; working with a model, making loose observations from objects around the studio, or looking at a photograph. Abstracting from a reference creates a very different kind of beginning. A line or shape created from observation vibrates with spacial energy, no matter if it resembles what you are looking at or trails off in another direction. Observation grounds your work in real space.

The gift of abstract forms is surrounding us at all times!

Some years ago I discovered the photographs of Joseph Podlesnik. I was immediately struck by his strong, unique compositions. He elevated ordinary scenes and everyday objects into stunning arrangements. His abstract design elements, strong diagonals, blocks of color, and sensitive use of value converged with a kind of edgy elegance. There was a clarity in his organization that I could relate to on a cellular level.

I hadn't been compelled to start a painting from a photograph in the past, but I recognized that we shared a common eye and I could feel the painting possibilities. Below, is one example of a photo that really caught my heart. I dove in and began to decipher the shapes, space and structure, with the willingness to veer off completely. I created a series of about 10 paintings that year in response to Joseph's photos. How wonderful to have such an inspiring road map! I never knew a trash can could be so beautiful, so essential to a composition.

Side Light, 40x40 oil on linen, 2017

Another approach was to work with a model. My foundational training was traditional and I have always loved figure drawing. Working abstractly for over twenty years, I fused the two approaches and comfortably pushed the boundaries of the life drawing. Using the model as my guide, I created a series of works on paper that vibrated somewhere between drawing and painting. The life force energy that remained in the completed pieces would not have been possible without following the curves, weight, and flow of the human form. Luckily, my model was always open and gracious when viewing these strange outcomes of herself.

You do not need any formal training in drawing to begin in this way. Even the smallest hint of observation and your lines will reflect your seeing, will reflect real space. This will add the satisfying illusion of volume to your work in unexpected ways. You can develop a relationship between your eyes and your hand, and build trust in what you're seeing and also in the marks you are making.

Work Station #10, 24x18, oil on paper, 2019

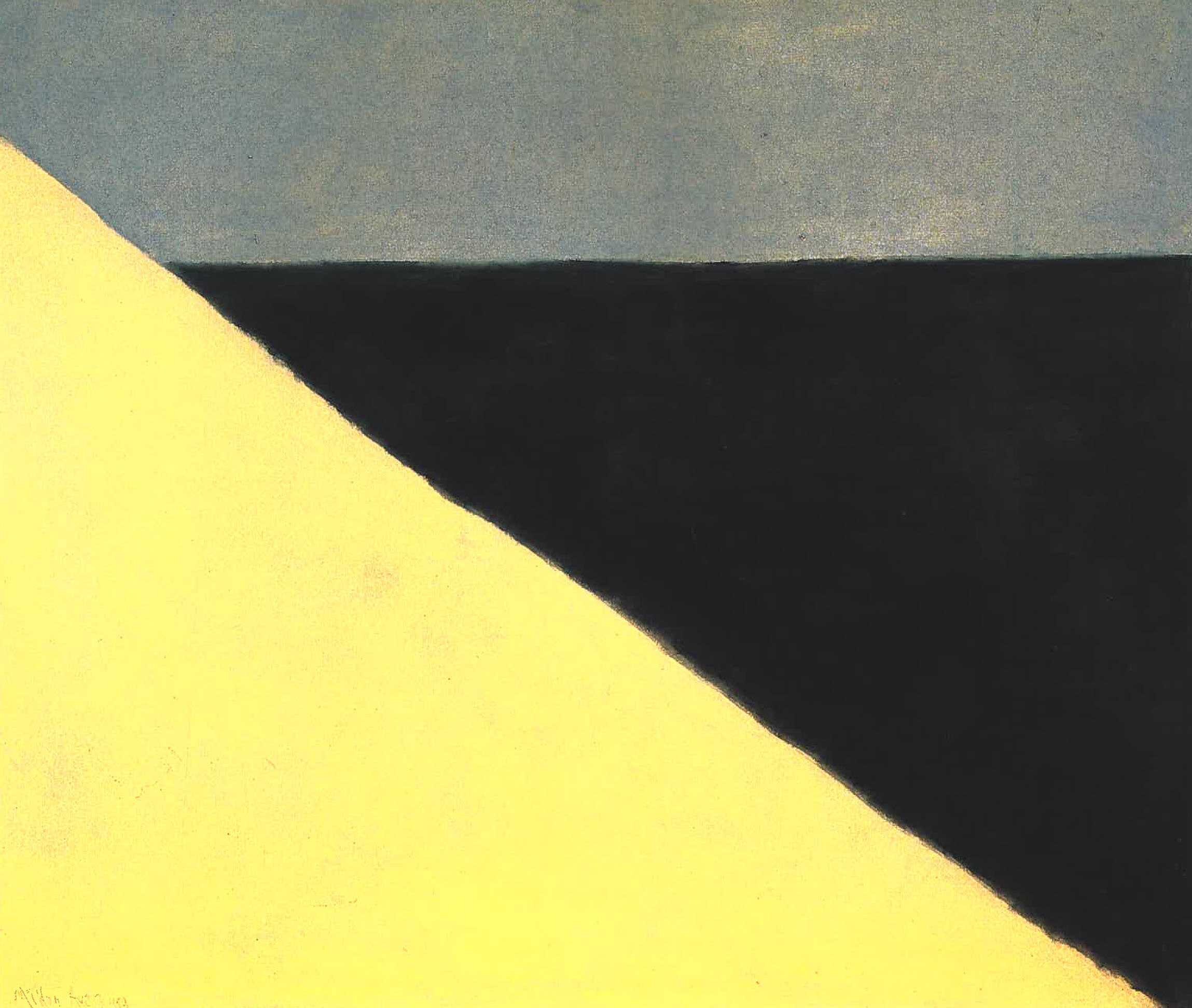

Milton Avery answers the question, "How much information do you need to include in a picture to activate a visual sensory memory in the viewer?" Even a fragmented or simplified shape can indicate vast space or a sense of place. Avery sifted out everything that was not essential. There are no extraneous forms, no extraneous details, no extraneous touches or elaborations in his images. In Avery's art, every object is stripped to its essential visual function.

The painting below confirms that any horizontal line, no matter how broken or simple, can claim the title horizon. Here, a very few flat shapes are locked into a simple design. The structure of the image is very lean, and very delicate with nothing tenuous to distract us.

Even while remaining mostly abstract, these indicators and associations are very comforting. We enjoy them, they make us feel grounded, within them we find the familiar. Whether a horizon line or a partially rendered object, the familiarity of a recognizable line allows us to enter into an inquisitive relationship with the painting.

Sand, Sea, Sky by Milton Avery; oil on canvas

Another less obvious way to abstract from observation, would be the capturing and transmuting of your personal experience with a place, space or object. Think Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series or Morandi's bottles. If you are a painter surrounded by a unique light, or landscape that so penetrates your senses, the act of translating that experience in paint may push through your arm and hand as a cooperative "must".

The artist, the paint, the place, and moments of observation, fuse as one.

Below is an image of the Maine coast which the British born, American abstract painter, John Walker, resolutely captures in his large-scale paintings. Inspired by this rough landscape and the surrounding sea, his work conveys the power and rhythms of this complex place and his attachment to it. If you were not familiar with the connection between this artist and this place, you may miss out on the amazing interpretation going on here. His work holds the essential elements of this tidal cove — a sulfurous mud flat when the tide is out and blue ocean when the tide is in.

Serenade II, vibrates with color and rhythm. Broad gesture abuts delicate lines attempting to capture what cannot be held in this landscape — air, water, ripples, and even the smell of the tidal cove. The viewer could be looking out at the ocean, above the ocean or on the ocean. The painting becomes the place without representing its source as it appears in the real world.

Serenade II, by John Walker; oil on canvas, 2015, 84 × 66 inches

I love the work of contemporary painter Ingrid Ellison. Another artist working in Maine, her intimate drawings and paintings are created through observation and reflection. She works in oil, mixed media and printmaking.

On the left, a journal entry depicts the process of recording and reflecting upon the natural world. The lines wander off towards the edge of the page. Some are thick, some thin and fleeting. The shape is reminiscent of the dried flower but remains open to other possible directions. As a journal entry, the form is flexible, a study. Less a final thought, then an open ended inquiry.

On the right, an oil painting on plywood. This piece feels like a transition from drawing to painting. Leaving the texture and rawness of the board, it retains the fresh, experimental feeling of working on paper. The paint layer, with its vibrant color and sometimes opaque, sometimes transparent texture, feels more decisive and final. It exists in some kind of in-between, with brilliant results. The secret language of seed pods and stems weaves together underneath a flat, citrus yellow silhouette. More than a depiction, it captures a feeling of things bursting forth. Another wonderful example of abstracting from life, simplifying an object down to its essence and capturing its innate vitality!

Seed Cycle, by Ingrid Ellison; oil and wax crayon on board, 2022

I recently discovered the semi-abstract work of British artist, Rosemary Vanns. Initially printmaking was her focus, but painting and mixed media are an equally important part of her work. Mark making and a neutral, earthy palette predominate in both disciplines. Both her still life work and landscapes are depicted as either semi-abstract or in a loose illustrative form.

In her words, "In regard to a reference — it is very studio based, where a small ladder, chair or pot or stone can catch my eye and conjure up a shape. They are glimpses, really, which then take on their own life organically. Sometimes when a shape or composition is not revealing what I had hoped, it is erased or covered over with further charcoal, paint or collage and more workings take place. A lot of my work is palimpsestic and in fact rely on this to allow them to shape shift"

How satisfying! The shapes are alive, grounded in observation, yet obscured in a way that guarantees our curiosity. You can almost follow the path of her hand, moving and making decisions to either include or obliterate the simple forms she sees around her studio. With an eraser or transparent wash we can trace the history within each work. There is little distraction from color, the warm neutral whites and rich blacks allow us to focus solely on the gestural drawing. The questions being asked are ones we should all have in our heads. What to leave? What to expand upon? What to smudge and pull outside of its original form? There is just enough information to recognize, but also imagine.

Cactus Bowl #1, by Rosemary Vanns; 38cm x 27cm, Charcoal collage on paper, 2022 (left)

Studio Inventory No.7, 55cm x 47cm, Acrylic, collage and charcoal on screen print, 2020 (right)

One of the repeated themes in all of the work shown here seems to be, simplifying down to the essential. Even if a reference is repeated, many lines overlapped, or elements obliterated and recovered, as artists, we are always faced with "what do I include, what do I discard, so that I arrive at the meat of the composition, or best incarnation of my experience and aesthetic?"

Working from observation gives us a great starting point — shapes, lines, structure, a sense of space and place. And best of all, life force energy!

Join my monthly newsletter and never miss a post

Each month I share explorations of master artists' works, elements of abstraction, and behind-the-scenes of my own painting journey, delivered to your inbox.